Growing up in the 1960s, my afternoons and summer vacations were spent working in a small bookstore run by an elderly Russian lady named Anna Blom, who paid me in “Wizard of Oz” books. Those stories of fantasy left a lasting impression. When it was time to buy my forever home, I found a place that gave my imagination free reign: a rather plain house on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill.

Built in 1906, the house was a simple, gabled Victorian. Inside, details including fir woodwork and oak floors showed a transition toward Arts & Crafts. Time had taken a toll; by 1986, it had been covered decades earlier with white vinyl siding outlined in black trim. Hardwood floors were hidden beneath dirty green carpeting. The only bath, upstairs, had a blue toilet and pink wallpaper installed upside down. The kitchen was harvest gold, avocado, and brown.

The house was, however, structurally sound and had good “bones”: A wide, open staircase greets visitors in the entry hall; the rich, aged fir woodwork had never been painted; original pocket doors still divide the living and dining rooms; a leaded-glass, built-in buffet with window seats runs across the back of the dining room. From day one, the daylight basement was clean and dry and had been partially finished with room for a second bath and even a kitchen.

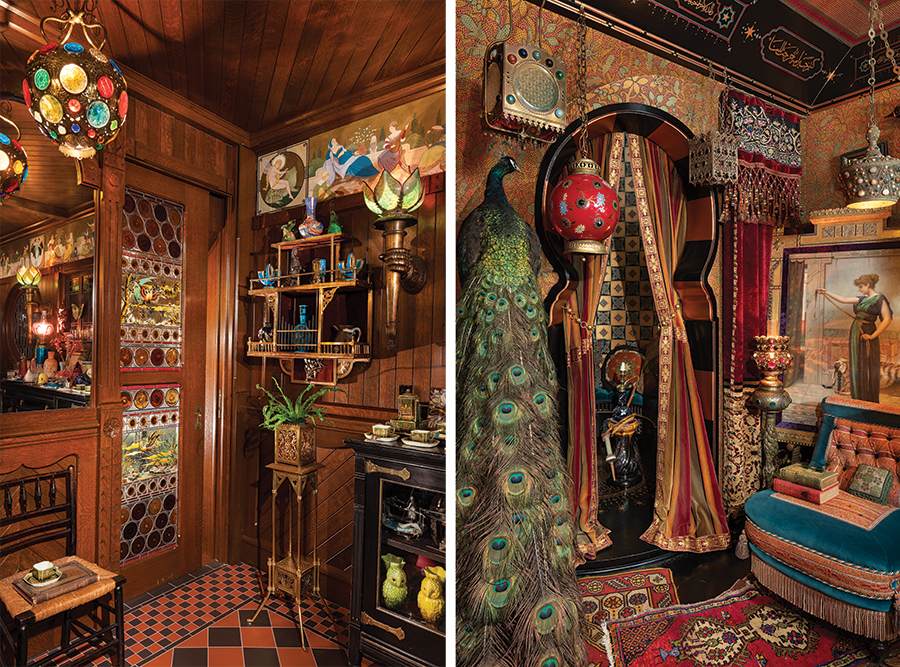

I started with the basics—replumbing out to the street, updating electrical, and insulating the attic. The yard was planted with colorful annuals and perennials. Then I began to decorate. Out went the green wall-to-wall; the oak floors with their mahogany borders were sanded and refinished. As first impressions are important, I found a ca. 1890 front door of oak inset with a stained-glass panel of Raphael to properly greet guests. I hung a ca. 1880 brass chandelier with multicolored shades in the center hall and added a custom burgundy-and-gold wallpaper of passion flowers from Christopher Hyland, topped by a hand-painted frieze of twirling vines. In the Victorian spirit, no surface was left plain. The ceiling was ornamented with a patterned fill outlined by a Persian foliate border from Schumacher, all 40 yards of paper patiently cut out by hand. Inspired by the peacock perched on the staircase in London’s 1880s Leighton House, I found a grand peacock in full display to preside over the upper staircase.

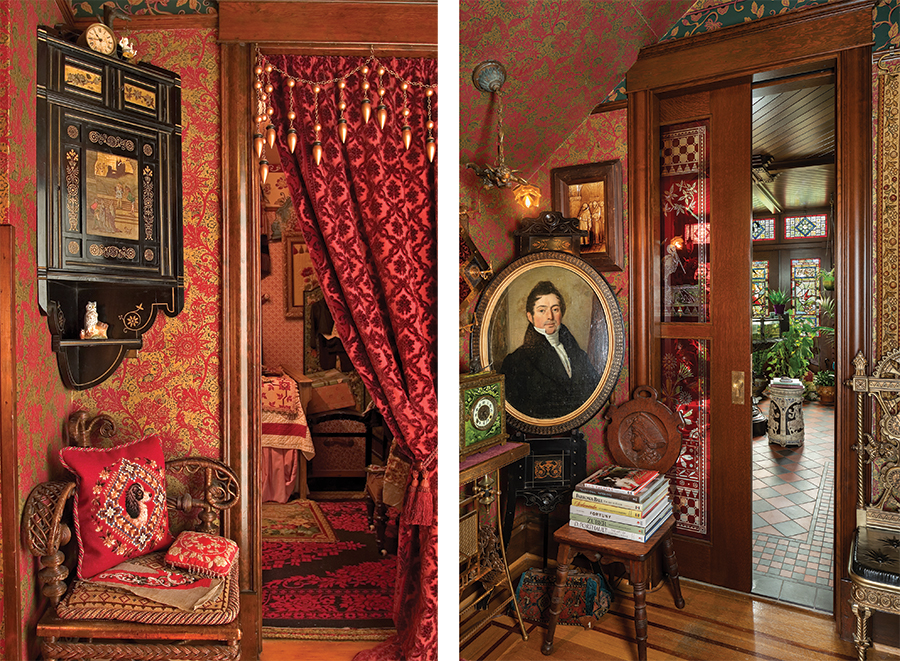

Continuing with a late-19th-century aesthetic, the parlor was papered in ‘Summer Street Damask’, a golden 1885 pattern from J.R. Burrows, above which hangs a Lincrusta frieze polychromed in sparkling silver, green, and gold. Vintage textiles were used throughout for upholstery: burgundy, green, and gold voided velvets for a tete-a-tete; an 1870s multicolored Kashmir shawl for an ebonized gentleman’s chair; a beaded, royal-purple Turkish embroidered panel for the seat of a carved stork chair.

At first I papered the parlor ceiling in a simple cracked-ice design, but soon decided that was not sufficiently elaborate. A few years later, I redid the ceiling in a complex design of multiple patterns anchored with corner blocks of sparrows in flight—a favorite Anglo–Japanese motif celebrating nature.

The opulent dinners of the age became a theme in the dining room. Walls were covered with ‘Persis Wall’, an English Aesthetic Movement paper with sprays of eucalyptus leaves and gilt blossoms on a gold ground; the polychromed Lincrusta frieze from the parlor repeats here. The original buffet’s leaded-glass doors were given a facelift with a spiderweb design replicated from a similar buffet in a ca. 1900 house in Portland. Windows in the small bay were swagged with Victorian voided velvets; I added roller shades, painted with a scene of the house, for privacy. I am a firm believer in Victorian excess, so soon every surface (dining table, buffet, plate rail) was filled with sets of brown and white transferware, gleaming silverplate, and multihued art glass and stemware.

Noting that my rooms were becoming High Victorian spaces, I realized the white vinyl siding outside had to go. We installed a red composition-shingle roof accented with a decorative floral pattern on the lower gables. A turret, I was sure, would be the right thing to upgrade the architecture, so I added one. Its painted Latin motto, Quo Amplius Eo Amplius, means something like “more beyond plenty”—indeed. Sunflowers, sea serpents, and owl heads were carved in mahogany to withstand Seattle’s wet climate; polychromed, they decorate the upper gables. The paint scheme is a fall palette of hunter green, gold, red, and black.

I tore out the 1970s rear kitchen to replace it with something more suitable: a Victorian conservatory. (My new, authentic re-creation kitchen in the English basement was not completed in time for this photo shoot, but stay tuned.) A set of four English stained-glass panels, ca. 1880, depicting colorful birds in a marsh, were turned into doors installed across the back of the room, opening to a small balcony overlooking the garden. A stained-glass firescreen by G.E. Cook, ca. 1875, was dismantled and recast as a window along the north wall, blocking a view to the house next door. Inspired by the Gothic Revival Jefferson Marketplace Library in New York City, I added a round, stained-glass window. An octagonal Fiske aquarium, ca. 1870, with a cast-iron base of stately storks now centers the room, adding humidity for the plants.

The back staircase leading from the conservatory to the basement was a sorry passageway. Inspired by the wonderful woodwork in the 1880s Cohen Bray House in Oakland, I lined the walls with oak paneling bordered by hand-carved sunflowers, with substantial carved braces framing the ceiling.

Upstairs, more stained glass was added to the window in the upper hall landing with a multi-hued, checkered and foliate panel by William MacPherson, ca. 1880, and the glass draped with ca. 1870 Turkey-red linen panels adorned with pearl and jet beads. A marble statue of Marguerite and Faust on the landing set an appropriately classical tone.

is glimpsed beyond. RIGHT: A sliding pocket door inset with antique, etched cranberry glass leads from the front hall to the conservatory. That space was formerly the kitchen.

The front bedroom has become an exotic Turkish retreat. The turret room was papered with a hand-silkscreened pattern from an 1890s wallpaper catalog. Undulating checkerboard squares are ringed above by four hand-painted panels from Edward Burne–Jones’s Pre-Raphaelite story of Pygmalion and Galatea. Far Eastern textiles and treasures fill the room.

The middle bedroom is simpler, for guests. Tucked into the eaves, the main bath was restored with a 19th-century ribcage shower, an elephant-trunk toilet, and a marble pedestal sink.

Want to see more?

Resources

wallpapers

Bradbury & Bradbury bradbury.com

J.R. Burrows burrows.com

Christopher Hyland christopherhyland.com

Schumacher Schumacher.com

‘Empire’

Lincrusta lincrusta.com

geometric tiles

Original Style (U.K.)originalstyle.com, through Tile Source tile-source.com

wall tiles

L’Esperance Tile Works lesperancetileworks.com

antiques

Singer Galleries, Seattle: singergalleries.com

textile artisans

Castillo’s Custom Upholsterers castillos@uphstudios.com

stained glass

all antique or salvaged for repurposing

Related Resources

victorian fretwork

Wabashiki Woodworks wabashikiwoodworks.com

wallpapers

Adelphi Paper Hangings adelphipaperhangings.com

Hand-block-printed historical wallpapers & borders 1750–1930

Bradbury & Bradbury Art Wallpapers bradbury.com

Silkscreen & digital papers including Victorian roomsets

color consulting

The Color People colorpeople.com

Custom paint color schemes for every style/era, nationwide

ornamental hardware

Notting Hill Decorative Hardware nottinghill-usa.com

Period-inspired cabinet hardware

The Swan Company swanpicturehangers.com

Unique picture hanging paraphernalia for period homes

window shades

Alameda Shade Shop shadeshop.com

Old-fashioned roller shades with trim options